In the last few months, I’ve seen a number of questions on Reddit and elsewhere about Emacs buffers, windows, and frames. These concepts are pretty confusing for a couple of reasons:

- They break some rules that we now take for granted in userland computing. (In an awesome way, though.)

- They use a different vocabulary that has nothing to do with what we usually call windows or buffers.

- Once you understand what they do, they seem obvious, which makes it hard to explain them to new users.

This post is a (hopefully) comprehensible explanation of what buffers, windows, and frames are in Emacs. Let’s start with some definitions and we’ll work from there:

Some Definitions

A buffer is an interface between Emacs and a file or process. It doesn’t have to be visible on the screen. You can (and sometimes will) have hundreds of buffers open in Emacs, but you’ll probably only have windows open to one or two at a time. Buffers hold text and each one has a unique name.

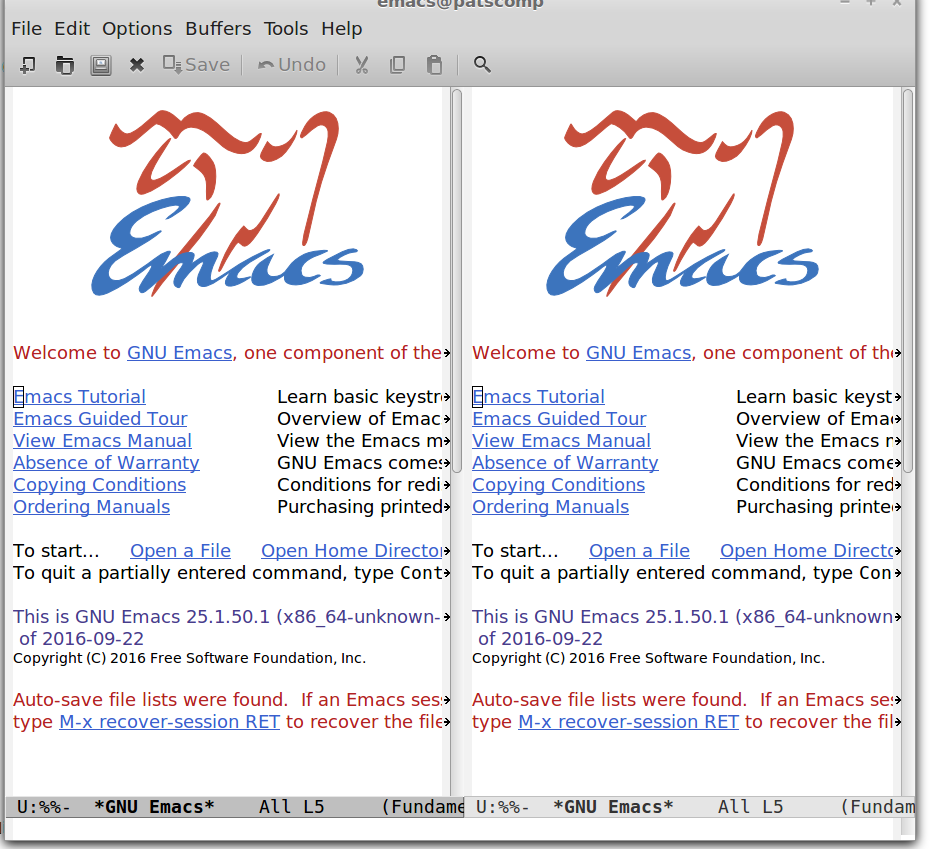

A window is a view onto a buffer. It allows you, the user, to see what’s going on inside that buffer. If the buffer is associated with a file, you’ll see the text of the file. If the buffer is associated with a process, such as a shell, you’ll see some representation of that process. You can split the current frame, which leaves you looking at two windows, like this:

A frame in Emacs is what you would call a window in most other contexts. They’re just windows in the normal sense of the word—you can drag them around the screen or close them with the `X` button or do whatever you do with windows. In the command line version of Emacs, you only ever have one frame. However, with the GUI (graphical) version you can open multiple frames, which looks like this:

Messing with Buffers, Windows, and Frames

OK, you’re still confused! Let’s try some commands that operate on buffers, windows, and frames. After doing this exercise, you should have a better idea of what buffers, windows, and frames are. You might also start to see why Emacs buffers are cool.

First, open Emacs. I’m going to assume that you’re using a fresh installation of Emacs. If you want to turn off your configuration to try this out, you can use

emacs -q

in the command line.

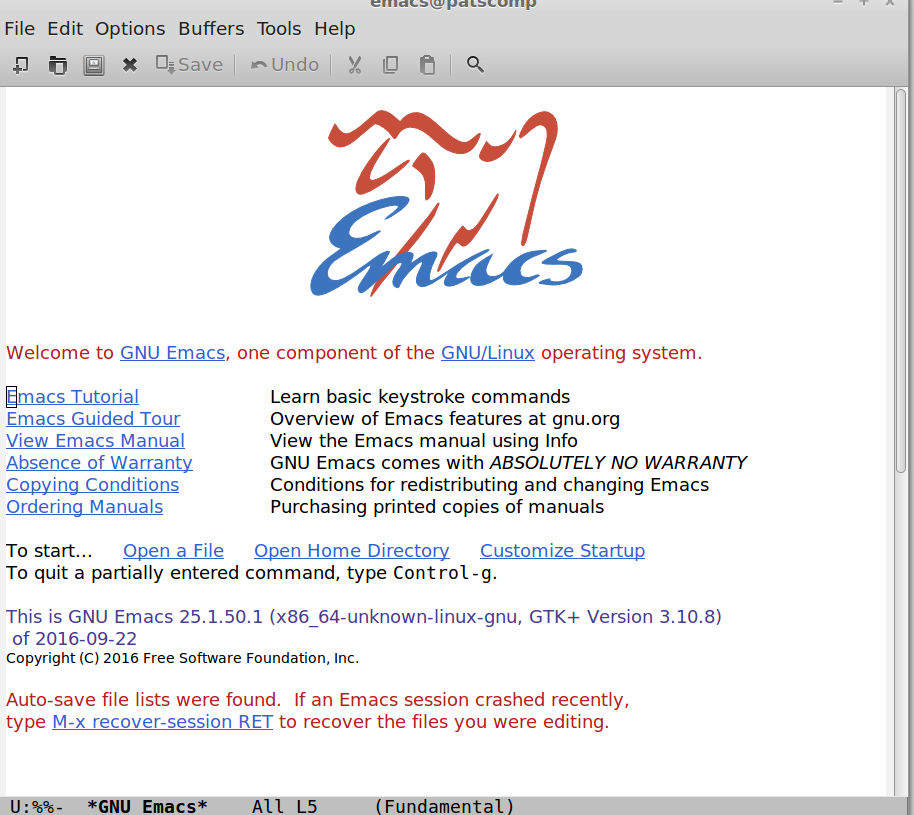

Once you have Emacs open, you should see the default splash screen:

Let’s try making a new window. Use

C-x 3

and you should see the screen split vertically. Now you have two windows, like this:

Though we have two windows open, they’re still “looking in” on only one buffer. Let’s change that.

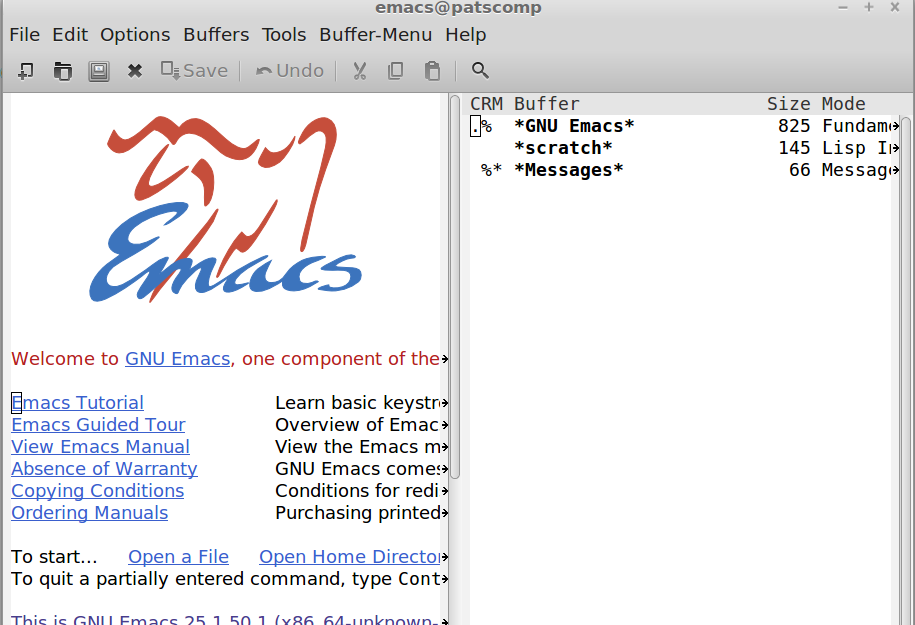

Though you’re only seeing one, there are actually three buffers open in Emacs—you just can’t see the other two right now. (Technically there are more, but some are hidden and are used internally by Emacs.) To see the other two, type

C-x C-b

A window will open that shows a list of current buffers. Press C-x o to switch windows (or click on the new window), move to the buffer called scratch, and press Enter. That window should change to a view of another buffer, which by default is there as a scratchpad. If you know the name of a buffer, you can also switch to it in the currently selected window with

C-x b

and then entering the name in the interactive prompt.

Finally, let’s try opening a new frame. (Note that if you’re using Emacs in a terminal, you won’t see a visual change with this command, though a new frame is still created.) Use

C-x 5 2

to open a new frame. This will create a separate “window” (in the non-Emacs sense) looking in on the same buffer. From this new frame, you still have access to all the open buffers in Emacs, so you can still use

C-x C-b

to explore open files and processes. You can also use

C-x 5 o

to switch between frames. (Thanks to user emacsclient on Reddit for pointing this out.)

Why Buffers Are Cool

Buffers are cool because they break with the idea that everything the computer does has to be currently visible to the user. If you’re using, say, iTunes, then there’s usually a representation of that program on the screen, even if it’s minimized. In Emacs, files and processes can still be open and easily accessible while staying entirely out of your way.

There are a few other advantages as well. If you’re working on a large text file, you can have buffers open to different segments of that file, and with narrowing you can even treat segments of the same file as if they were completely different files in their own right. The consistent buffer interface means that any command that works on one buffer is likely to work on others, which makes buffers easy to manipulate and script.

That’s the weird and wonderful world of Emacs buffers, windows, and frames for you. Drop me a line if you find any of these explanations unclear.

Resources

buffers, windows, and frames on Blasphemous Bits

Emacs terminology on the Emacs wiki

Absolute Beginner’s Guide to Emacs on Jessica Hamrick’s blog (Good list of buffer-, window-, and frame-manipulating commands)

Using Multiple Buffers

Working with Windows and Frames by Hack Emacs

“What’s the difference between a buffer, a file, a window, and a frame?” on StackExchange